Psycho-social Development

Erik Erikson's theory of Psycho social development is one of the best-known theories of personality

His ideas were greatly influenced by Freud, going along with Freud's theory regarding the structure and topography of personality.

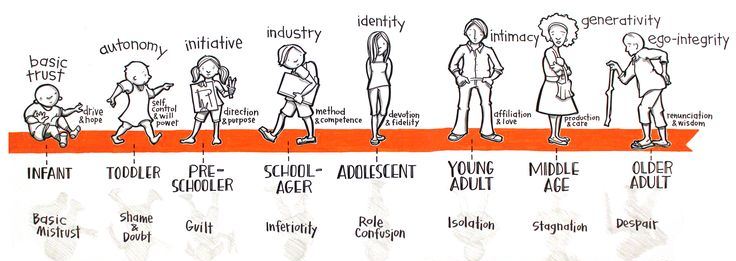

Erikson developed a theory of personality that focuses on psychosocial crises that confront the growing individual. He accepts Freud's concept of ego but not the ideas of the Id and Super-Ego. Erikson's scheme, human being pass through eight stages of development. At each stage the individual must face a crises of adjusting to the social and cultural environment. According to Erikson, the Ego develops as it successfully resolves crises that are distinctly social in nature. These involve establishing a sense of trust in others,developing a sense of identity in society and helping the next generation for the future.

Erikson proposed a lifespan model of development, taking in five stages up to the age of 18 years and three further stages beyond, well into adulthood. Erikson suggests that there is still plenty of room for continued growth and development throughout one’s life. Erikson puts a great deal of emphasis on the adolescent period, feeling it was a crucial stage for developing a person’s identity.

Like Freud and many others, Erik Erikson maintained that personality develops in a predetermined order, and builds upon each previous stage. This is called the epigenic principle.

The outcome of this 'maturation timetable' is a wide and integrated set of life skills and abilities that function together within the autonomous individual. However, instead of focusing on sexual development (like Freud), he was interested in how children socialize and how this affects their sense of self.

A BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF THE MAN BEHIND THE STAGES OF PSYCHO SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT

Birth and Death:

- Erik Erikson was born June 15, 1902.

- He died May 12, 1994.

Childhood: Early Questions About Identity

Erik Erikson was born June 15, 1902 in Frankfurt, Germany.

"The common story was that his mother and father had separated before his birth, but the closely guarded fact was that he was his mother's child from an extramarital union

He never saw his birth father or his mother's first husband," reported Erikson's obituary that appeared in The New York Times following his death 1994.

His young Jewish mother, Karla Abrahamsen, raised Erik by herself for a time before marrying a physician, Dr. Theodor Homberger. The fact that Homberger was not in fact his biological father was concealed from him for many years. When he finally did learn the truth, Erikson was left with a feeling of confusion about who he really was.

This early experience helped spark his interest in the formation of identity. While this may seem like merely an interesting anecdote about his heritage, the mystery over Erikson's biological parentage served as one of the key forces behind his later interest in identity formation. He would later explain that as a child he often felt confused about who he was and how he fit into to his community.

His interest in identity was further developed based upon his own experiences in school. At his Jewish temple school he was teased for being a tall, blue-eyed, and blonde Nordic-looking boy who stood out among the rest of the kids.

At grammar school, he was rejected because of his Jewish background. These early experiences helped fuel his interest in identity formation and continued to influence his work throughout his life.

Career:

It is interesting to note that Erikson never received a formal degree in medicine or psychology. While studying at the Das Humanistische Gymnasium, he was primarily interested in subjects such as history, Latin, and art. His stepfather, a doctor, wanted him to go to medical school, but Erikson instead did a brief stint in art school. He soon dropped out and spent time wandering Europe with friends and contemplating his identity.

It was an invitation from a friend that sent him to take a teaching position at a progressive school created by Dorothy Burlingham, a friend of Anna Freud's. Anna soon noticed Erikson rapport with children and encouraged him to formally study psychoanalysis.

Erikson ultimately received two certificates from the Montessori teachers association and from the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute.

He continued to work with Burlingham and Freud at the school for several years, met Sigmund Freud at a party, and even became Anna Freud's patient.

"Psychoanalysis was not so formal then," he recalled. "I paid Miss Freud $7 a month, and we met almost every day. My analysis, which gave me self-awareness, led me not to fear being myself. We didn't use all those pseudoscientific terms then -- defense mechanism and the like -- so the process of self-awareness, painful at times, emerged in a liberating atmosphere."

He met a Canadian dance instructor named Joan Serson who was also teaching at the school where he worked. The couple married in 1930 and went on to have three children. His son, Kai T. Erikson, is a noted American sociologist.

Erikson moved to the United States in 1933 and, despite having no formal degree, was offered a teaching position at Harvard Medical School. He also changed his name from Erik Homberger to Erik H. Erikson, perhaps as a way to forge is own identity. In addition to his position at Harvard, he also had a private practice in child psychoanalysis.

Later, he held teaching positions at the University of California at Berkeley, Yale, the San Francisco Psychoanalytic Institute, Austen Riggs Center, and the Center for Advanced Studies of the Behavioral Sciences.

He published a number of books on his theories and research, including Childhood and Society and The Life Cycle Completed. His book Gandhi's Truth was awarded a Pulitzer Prize and a national Book Award.

Erikson was a neo-Freudian psychologist who accepted many of the central tenants of Freudian theory, but added his own ideas and beliefs. His theory of psychosocial development is centered on what is known as the epigenetic principle, which proposes that all people go through a series of eight stages. At each stage, people face a crisis that needs to be successfully resolved in order to develop the psychological quality central to each stage.

The eight stage of Erikson's psychosocial theory are something that every psychology student learns about as they explore the history of personality psychology. Much like psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, Erikson believed that personality develops in a series of stages. Erikson’s theory marked a shift from Freud's psychosexual theory in that it describes the impact of social experience across the whole lifespan instead of simply focusing on childhood events.

While Freud's theory of psychosexual development essentially ends at early adulthood, Erikson's theory described development through the entire lifespan from birth until death.

Contributions to Psychology

Erik Erikson spent time studying the cultural life of the Sioux of South Dakota and the Yurok of northern California. He utilized the knowledge he gained of cultural, environmental, and social influences to further develop his psychoanalytic theory.

While Freud’s theory had focused on the psychosexual aspects of development, Erikson’s addition of other influences helped to broaden and expand psychoanalytic theory. He also contributed to our understanding of personality as it is developed and shaped over the course of the lifespan.

His observations of children also helped set the stage for further research. "You see a child play," he was quoted in his New York Times obituary, "and it is so close to seeing an artist paint, for in play a child says things without uttering a word. You can see how he solves his problems. You can also see what's wrong. Young children, especially, have enormous creativity, and whatever's in them rises to the surface in free play."

"Hope is both the earliest and the most indispensable virtue inherent in the state of being alive. If life is to be sustained hope must remain, even where confidence is wounded, trust impaired."

- Erik Erikson

"Hope is both the earliest and the most indispensable virtue inherent in the state of being alive. If life is to be sustained hope must remain, even where confidence is wounded, trust impaired."

- Erik Erikson

Psychosocial Stages

| 0-2 years | Hope | Basic trust vs. mistrust | Mother | Can I trust the world? | Feeding, abandonment |

| 2–4 years | Will | Autonomy vs. shame and doubt | Parents | Is it okay to be me? | Toilet training, clothing themselves |

| 4–5 years | Purpose | Initiative vs. guilt | Family | Is it okay for me to do, move, and act? | Exploring, using tools or making art |

| 5–12 years | Competence | Industry vs. inferiority | Neighbors, school | Can I make it in the world of people and things? | School, sports |

| 13–19 years | Fidelity | Identity vs. role confusion | Peers, role model | Who am I? Who can I be? | Social relationships |

| 20–39 years | Love | Intimacy vs. isolation | Friends, partners | Can I love? | Romantic relationships |

| 40–64 years | Care | Generativity vs. stagnation | Household, workmates | Can I make my life count? | Work, parenthood |

| 65-death | Wisdom | Ego integrity vs. despair | Mankind, my kind | Is it okay to have been me? | Reflection on life |

1. Hopes: trust vs. mistrust (oral-sensory, birth – 2 years)

Is the world a safe place or is it full of unpredictable events and accidents waiting to happen?

Erikson's first psychosocial crisis occurs during the first year or so of life (like Freud's oral stage of psychosexual development). The crisis is one of trust vs. mistrust.

During this stage the infant is uncertain about the world in which they live. To resolve these feelings of uncertainty the infant looks towards their primary caregiver for stability and consistency of care.

If the care the infant receives is consistent, predictable and reliable, they will develop a sense of trust which will carry with them to other relationships, and they will be able to feel secure even when threatened.

Success in this stage will lead to the virtue of hope. By developing a sense of trust, the infant can have hope that as new crises arise, there is a real possibility that other people will be there are a source of support. Failing to acquire the virtue of hope will lead to the development of fear.

For example, if the care has been harsh or inconsistent, unpredictable and unreliable, then the infant will develop a sense of mistrust and will not have confidence in the world around them or in their abilities to influence events.

This infant will carry the basic sense of mistrust with them to other relationships. It may result in anxiety, heightened insecurities, and an over feeling of mistrust in the world around them.

Consistent with Erikson's views on the importance of trust, research by Bowlby and Ainsworth has outlined how the quality of the early experience of attachment can affect relationships with others in later life.

2. Will: autonomy vs. shame and doubt (muscular-anal, 2–4 years)

The child is developing physically and becoming more mobile. Between the ages of 18 months and three, children begin to assert their independence, by walking away from their mother, picking which toy to play with, and making choices about what they like to wear, to eat, etc.

The child is discovering that he or she has many skills and abilities, such as putting on clothes and shoes, playing with toys, etc. Such skills illustrate the child's growing sense of independence and autonomy. Erikson states it is critical that parents allow their children to explore the limits of their abilities within an encouraging environment which is tolerant of failure.

For example, rather than put on a child's clothes a supportive parent should have the patience to allow the child to try until they succeed or ask for assistance.

So, the parents need to encourage the child to becoming more independent whilst at the same time protecting the child so that constant failure is avoided.

A delicate balance is required from the parent. They must try not to do everything for the child but if the child fails at a particular task they must not criticize the child for failures and accidents (particularly when toilet training). The aim has to be “self control without a loss of self-esteem” (Gross, 1992). Success in this stage will lead to the virtue of will.

If children in this stage are encouraged and supported in their increased independence, they become more confident and secure in their own ability to survive in the world.

If children are criticized, overly controlled, or not given the opportunity to assert themselves, they begin to feel inadequate in their ability to survive, and may then become overly dependent upon others, lack self-esteem, and feel a sense of shame or doubt in their own abilities.

If children in this stage are encouraged and supported in their increased independence, they become more confident and secure in their own ability to survive in the world.

If children are criticized, overly controlled, or not given the opportunity to assert themselves, they begin to feel inadequate in their ability to survive, and may then become overly dependent upon others, lack self-esteem, and feel a sense of shame or doubt in their own abilities.

3.Purpose: initiative vs. guilt (locomotor-genital, preschool, 4–5 years)

Around age three and continuing to age five, children assert themselves more frequently. These are particularly lively, rapid-developing years in a child’s life. According to Bee (1992) it is a “time of vigor of action and of behaviors that the parents may see as aggressive".

During this period the primary feature involves the child regularly interacting with other children at school. Central to this stage is play, as it provides children with the opportunity to explore their interpersonal skills through initiating activities.

Children begin to plan activities, make up games, and initiate activities with others. If given this opportunity, children develop a sense of initiative, and feel secure in their ability to lead others and make decisions.

Conversely, if this tendency is squelched, either through criticism or control, children develop a sense of guilt. They may feel like a nuisance to others and will therefore remain followers, lacking in self-initiative.

The child takes initiatives which the parents will often try to stop in order to protect the child. The child will often overstep the mark in his forcefulness and the danger is that the parents will tend to punish the child and restrict his initiatives too much.

It is at this stage that the child will begin to ask many questions as his thirst for knowledge grows. If the parents treat the child’s questions as trivial, a nuisance or embarrassing or other aspects of their behavior as threatening then the child may have feelings of guilt for “being a nuisance”.

Too much guilt can make the child slow to interact with others and may inhibit their creativity. Some guilt is, of course, necessary, otherwise the child would not know how to exercise self control or have a conscience.

A healthy balance between initiative and guilt is important. Success in this stage will lead to the virtue of purpose.

4. Competence: industry vs. inferiority (latency, 5–12 years)[edit]

Children are at the stage (aged 5 to 12 yrs) where they will be learning to read and write, to do sums, to do things on their own. Teachers begin to take an important role in the child’s life as they teach the child specific skills.

It is at this stage that the child’s peer group will gain greater significance and will become a major source of the child’s self esteem. The child now feels the need to win approval by demonstrating specific competencies that are valued by society, and begin to develop a sense of pride in their accomplishments.

If children are encouraged and reinforced for their initiative, they begin to feel industrious and feel confident in their ability to achieve goals. If this initiative is not encouraged, if it is restricted by parents or teacher, then the child begins to feel inferior, doubting his own abilities and therefore may not reach his or her potential.

If the child cannot develop the specific skill they feel society is demanding (e.g. being athletic) then they may develop a sense of inferiority. Some failure may be necessary so that the child can develop some modesty. Yet again, a balance between competence and modesty is necessary. Success in this stage will lead to the virtue of competence.

5. Fidelity: identity vs. role confusion (adolescence, 13–19 years)

During adolescence (age 12 to 18 yrs), the transition from childhood to adulthood is most important. Children are becoming more independent, and begin to look at the future in terms of career, relationships, families, housing, etc. The individual wants to belong to a society and fit in.

This is a major stage in development where the child has to learn the roles he will occupy as an adult. It is during this stage that the adolescent will re-examine his identity and try to find out exactly who he or she is. Erikson suggests that two identities are involved: the sexual and the occupational.

According to Bee (1992), what should happen at the end of this stage is “a reintegrated sense of self, of what one wants to do or be, and of one’s appropriate sex role”. During this stage the body image of the adolescent changes.

Erikson claims that the adolescent may feel uncomfortable about their body for a while until they can adapt and “grow into” the changes. Success in this stage will lead to the virtue of fidelity.

Fidelity involves being able to commit one's self to others on the basis of accepting others, even when there may be ideological differences.

During this period, they explore possibilities and begin to form their own identity based upon the outcome of their explorations. Failure to establish a sense of identity within society ("I don’t know what I want to be when I grow up") can lead to role confusion. Role confusion involves the individual not being sure about themselves or their place in society.

In response to role confusion or identity crisis an adolescent may begin to experiment with different lifestyles (e.g. work, education or political activities). Also pressuring someone into an identity can result in rebellion in the form of establishing a negative identity, and in addition to this feeling of happiness.

6. Love: intimacy vs. isolation (young adulthood, 20–24, or 20–39 years)

6. Love: intimacy vs. isolation (young adulthood, 20–24, or 20–39 years)

Occurring in young adulthood (ages 18 to 40 yrs), we begin to share ourselves more intimately with others. We explore relationships leading toward longer term commitments with someone other than a family member.

Successful completion of this stage can lead to comfortable relationships and a sense of commitment, safety, and care within a relationship. Avoiding intimacy, fearing commitment and relationships can lead to isolation, loneliness, and sometimes depression. Success in this stage will lead to the virtue of love.

7. Care: generativity vs. stagnation (middle adulthood, 25–64, or 40–64 years)

During middle adulthood (ages 40 to 65 yrs), we establish our careers, settle down within a relationship, begin our own families and develop a sense of being a part of the bigger picture.

We give back to society through raising our children, being productive at work, and becoming involved in community activities and organizations.

By failing to achieve these objectives, we become stagnant and feel unproductive. Success in this stage will lead to the virtue of care.

8. Wisdom: ego integrity vs. despair (late adulthood, 65 – death)

As we grow older (65+ yrs) and become senior citizens, we tend to slow down our productivity, and explore life as a retired person. It is during this time that we contemplate our accomplishments and are able to develop integrity if we see ourselves as leading a successful life.

Erik Erikson believed if we see our lives as unproductive, feel guilt about our past, or feel that we did not accomplish our life goals, we become dissatisfied with life and develop despair, often leading to depression and hopelessness.

Success in this stage will lead to the virtue of wisdom. Wisdom enables a person to look back on their life with a sense of closure and completeness, and also accept death without fear.

PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS:

Erikson's Identity vs. Role Confusion in Adolescent Development

Adolescents often rebel against their parents and try out new and different things. In this lesson, we'll look at Erik Erikson's theory of adolescent development, including how resolving a psychosocial crisis can lead to fidelity in interpersonal relationships.

Adolescent Development

Chaya is 15, and lately she's been driving her parents a little crazy. She used to be a very obedient daughter. She dressed appropriately, got good grades and generally did what her parents expected her to do. All in all, she was a good girl.

But recently, things have changed. She's started dressing differently, and she dyed her hair blue. She isn't listening to her parents as much anymore. Just last week, she told her mom that she wasn't going to become a doctor, like her parents want. In fact, she said that she might not even go to college!

Chaya is in adolescence, or the period of life between childhood and adulthood. This is usually seen as being between ages 12 and 20. Like Chaya, many adolescents begin to change and rebel. They explore new ideas about themselves and their place in the world. Psychologist Erik Erikson said that this exploration is part of a psychosocial crisis, or a developmental period when a person has to resolve a conflict in his or her own life.

Let's look closer at the psychosocial crisis that is common in adolescence, identity versus role confusion, and what happens when an adolescent resolves that conflict.

Identity vs. Role Confusion

Remember Chaya? She's rebelling against her parents, changing before their very eyes. She's resisting their expectations of her and trying out new and different aspects of herself.

Chaya is displaying the adolescent psychosocial crisis that will either lead her to identity, or knowing who she is and what she believes, or to role confusion, or not being sure of who she is or what she believes. Remember that this is called a psychosocial crisis, or sometimes a psychosocial conflict. In fact, a key part of adolescence is exploring the two parts of the word 'psychosocial.'

Think about it like this: Chaya is exploring and experimenting with different aspects of herself. She is dressing differently, dying her hair, making up her own mind about college and other aspects of her life. These are all part of her inner self: her psychology, which is the first part of psychosocial.

On the other hand, her parents and the rest of society expect certain things from her. They expect her to dress and act like a girl. They expect her to behave and have her hair a certain way. They pressure her to do certain things and be certain things. Society is the second part of psychosocial, and it's all about external forces.

In adolescence, many people find that the tension between the internal forces of the self and the external forces of society is particularly high. Just like Chaya, adolescents begin to explore different roles, or ideas about themselves. They may change their behavior or physical looks. They might change their minds about what they want to do with their lives. They are experimenting with who they are and what that means.

If Chaya's parents and friends are supportive of her and allow some amount of experimentation with roles, Chaya will likely end up with a cohesive, full identity that expresses who she is.

But what if her parents and friends are not supportive of her? What if Chaya lives in a society that denies her the ability to experiment with roles and explore who she is as an individual? Well, then Chaya will likely end up in role confusion. She might not feel like she knows who she is deep down, or she might go through life constantly playing the part that her parents or friends want her to play.

Fidelity

So, what's the big deal with identity and role confusion? Why should Chaya develop cohesive identity?

There are many benefits to having a cohesive identity.For one thing, people who end up in Role Confusion often feel dissatisfied and kind of drift from one thing to another. They might have trouble figuring out what they want from life or relationships.

But most importantly, people in Role Confusion do not develop Fidelity, which Erikson defined as being able to relate to people in a sincere, genuine way. Good relationships have a strong foundation of fidelity.

If an adolescent, like Chaya is able to resolve the identity versus role confusion conflict and end up with a cohesive identity, she will be able to display fidelity in her relationship with others. If she doesn't end up with a cohesive identity, she is likely not going to have fidelity in her relationship.

REFERENCES:

- http://study.com/academy/lesson/eriksons-identity-vs-role-confusion-in-adolescent-development.html

- http://www.simplypsychology.org/Erik-Erikson.html

- http://psychology.about.com/od/psychosocialtheories/fl/Psychosocial-Stages-Summary-Chart.htm

- http://psychology.about.com/od/profilesofmajorthinkers/p/bio_erikson.htm

- Psychology Today and Tomorrow By Mcneil, EltonB., et al

- Understanding Psychology (Fourth Edition) by Perrin, Linda

Yes, great US Military force. Also, in his post you have given a chance to listen about US Military. I really appreciate your work. Thanks for sharing it.

ReplyDeletelook at this now

Hello -- a lovely post! I am interested in obtaining the graphic (Erikson's 8 stages) at the the top of this page; is it yours, and if so, I'd like to request its use in an educational video. If it's not yours, do you know its source (i.e. where I can request permission for its use)? Thank you!

ReplyDelete